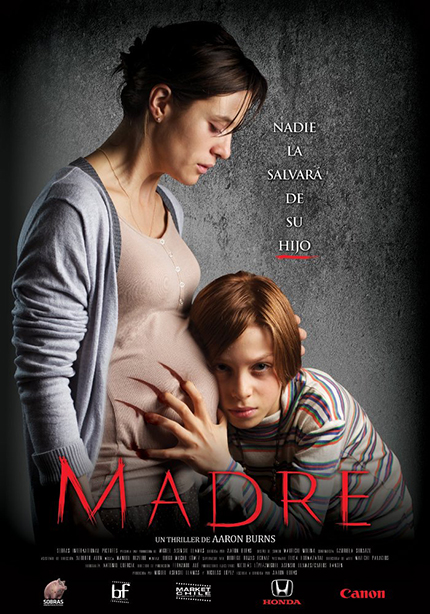

Just ahead of its SXSW premiere, Netflix acquired global streaming rights to this Chilean psychological thriller by writer/director Aaron Burns. Drawing clear inspiration from classic thrillers like Rosemary’s Baby, this outing sees a pregnant mother, Diane, alone taking care of her unruly autistic first born, Martin, while her husband is overseas for work. At her breaking point, she meets Luz, an older Filipino woman with a penchant for improving Martin’s behavior. Though Luz initially seems like a godsend, Diane begins to suspect that Luz is really a voodoo practitioner out to get her family.

Any film that leaves you thinking about its implications has clearly done something right.

From a basic narrative standpoint, the plot hits all of the familiar beats of psychological thrillers before. Prior to Luz’s arrival, Diane was on the verge of a breakdown. Her son, uncommunicative and prone to major physical tantrums, doesn’t seem to harbor any fond feelings toward her. Feeling alone without her husband’s support made Luz’s entrance into her life all the more welcome. From there, the narrative moves along the familiar bait-and-switch plot points that have worked so effectively in the past. With Diane becoming more and more isolated, it becomes less clear whether the stress is making her paranoid or if there really is something off about Luz.

For a short run time, the pacing in the middle sags a bit. Moments that are meant to drive Diane toward the climax don’t go quite as far as they need to go to ramp up the psychological aspect. There’s a bug in the ear gag that should work, but isn’t nearly as unnerving as it sounds on paper. In other words, Burns plays it too safe. Hallucinatory sequences are far more effective, if not a bit familiar. The biggest flaw in the story, however, is Luz’s promise to cure Martin’s autism. Though she seems to do exactly that, Diane’s quick acceptance of this bold promise makes it difficult to suspect belief. It’s an intentional character flaw, but not one that translates well on screen.

Burns’ end goal is a far more ambitious endeavor that proves quite tricky to achieve. He wants the audience’s allegiance to waiver back and forth between Luz and Diane. In that he’s succeeded, perhaps too well. The saintly Luz is a stark contrast from the bratty Diane. Between Diane’s poor handling of her own son, and the shrewish way she views her life, she doesn’t exactly garner viewer sympathy. Ultimately, it’s Burns’ character work that makes this film work, and the interesting thesis that comes together at the end. The simple, bright cinematography contributes to keeping the focus on the interplay between Diane and Luz.

Though at times too derivative and too safe, Burns still pulls together an engrossing thriller.

Though at times too derivative and too safe, Burns still pulls together an engrossing thriller. It’s a light psychological thriller with interesting cultural observations made. It’s imperfect, and doesn’t go nearly as far as it should, but it still entertains nonetheless. Burns waits until the correct moment to pull back the curtain on the reveal, and it’s a satisfying conclusion. While some psychological thrillers are given ambiguous endings, that’s not the case here. There is a clear ending; it’s just how you feel about it that will be ambiguous. Which means that Burns’ film proved successful, as any film that leaves you thinking about its implications has clearly done something right.

Madre made its world premiere at SXSW on March 11, 2017, and will be available on Netflix sometime later this year.