One of William Blake’s core principles—and perhaps one of his more controversial in its day—was a formal rejection of organized religion. He believed it was more of a social constraint, one that held Christians back from a more liberating and fulfilling spiritual life.

This tenet of Blake’s philosophy is presented as a clue for the audience and the protagonist alike in ‘Saint Maud’. Maud herself reads his words out loud, quoting from a book that her patient has given her. And the extent to which she heeds Blake’s advice determines which side of the tipping point between comedy and tragedy she lands on.

That’s the essence of the horror on display in ‘Saint Maud’—what can happen when we ignore the lifelines in front of us and continue to dig our own graves instead. In that sense, it’s more of a psychological horror film than a religious one, despite what you may see on the surface.

It’s more of a psychological horror film than a religious one, despite what you may see on the surface.

The first images we see are the catalysts for the journey ahead: a young nurse devastated by the death of a patient in her care. The loss is affecting enough that Maud leaves her old life behind in favor of one centered around piety and service. She’s still a nurse, and a decent one at that, but she’s become more concerned with saving souls than saving lives.

When she begins taking care of a dying woman named Amanda—the one who gifts Maud a book of Blake’s work—her passion turns to obsession. Amanda lives what Maud believes to be a life of sin, made all the more concerning given that her days are numbered.

The core journey of ‘Saint Maud’ is how Maud navigates her relationship with Amanda, the woman that she believes God has placed in her physical and spiritual care; her faith in God hinges upon her ability to save Amanda. She internalizes her struggle to the point of self-flagellation, elevating her methods of punishment as her crusade escalates, until the consequences of her zealotry begin to spiral into something much more sinister.

Her faith in God hinges upon her ability to save Amanda.

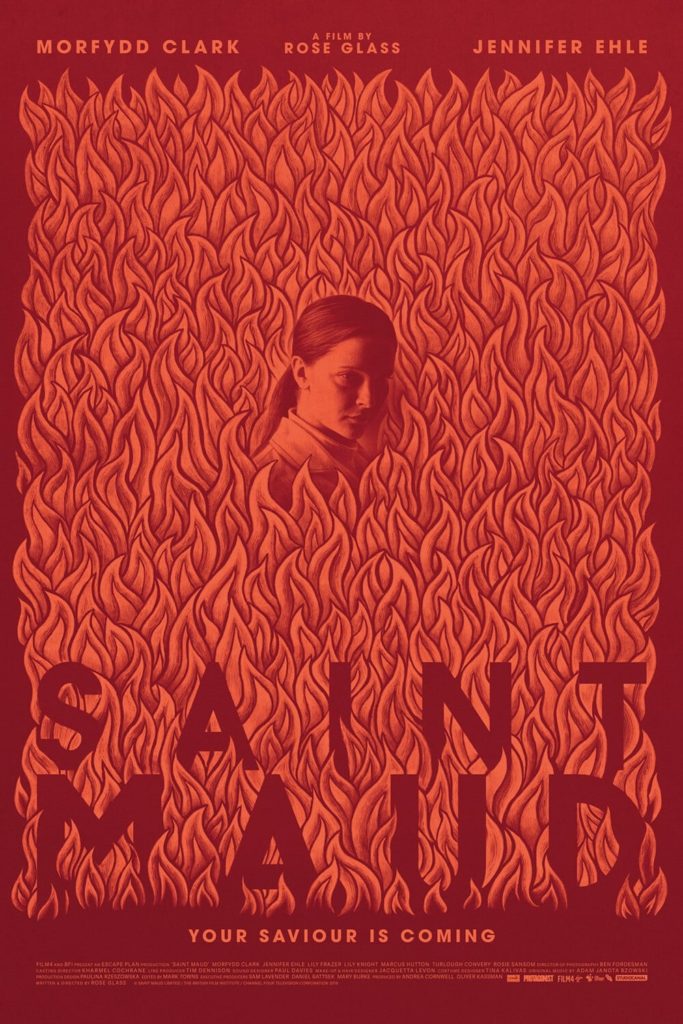

The film itself is anchored almost entirely by the lead performance, and Morfydd Clark does not disappoint. A relatively unknown young Welsh actress before this role, she’s now earned a career-defining achievement that will stick with horror fans in the way that A24’s comparable leading ladies—Anya Taylor-Joy, Florence Pugh, and Kiernan Shipka come to mind—have in the past.

While Clark is front and center, the film around her isn’t exactly lacking. The cinematography, canvassing a small seaside town in England with one particularly flashy block, is sturdy without being showy. In similar fashion, the special effects are sparse but used effectively, even when they might not look realistic. And the sharp editing of the film’s final shot is such a shock that you might not blink until the credits have rolled.

The sharp editing of the film’s final shot is such a shock that you might not blink until the credits have rolled.

The pacing is a bit of a struggle at first, as the film takes more than half of its brief runtime to really get going. But it is certainly not without payoff—what begins as a simmer eventually turns into a boil until suddenly the room is on fire (and so are you).

As with other cautionary tales, Saint Maud isn’t exactly an uplifting joy ride, but writer/director Rose Glass hits every mark that she aimed for in her film debut. And though the film was robbed of a proper theatrical release in 2020, it’s destined to be one of the most talked-about horror films of 2021.

‘Saint Maud’ hits theaters on January 29 and will be available on VOD and streaming on Epix starting February 12.

‘Saint Maud’ Filters Psychological Horror Through a Religious Lens

Compelling

‘Saint Maud’ blends psychological horror with religious themes to deliver a grim but gripping character study driven by Morfydd Clark’s performance.