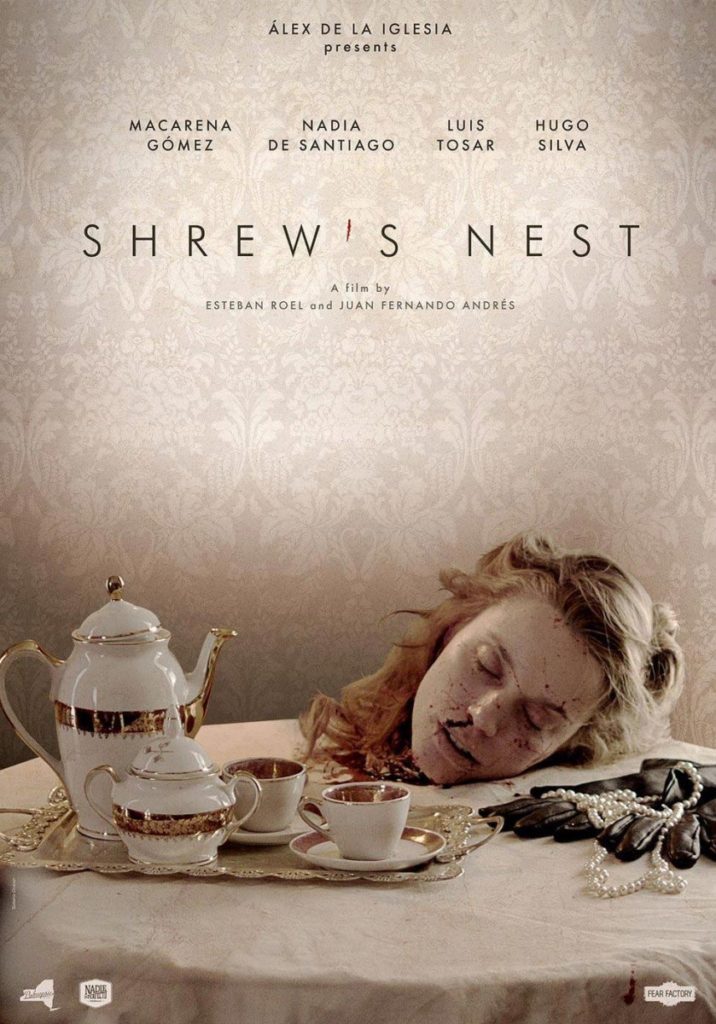

When Shrew’s Nest screened at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2014, one movie that it kept evoking for everyone was Misery, Rob Reiner’s 1990 adaptation of the Stephen King novel. While buzz like that probably sold quite a few tickets at the Fest, Shrew’s Nest is actually a far more grisly affair than Misery, one with a lot more lurking below the surface, as well as a distinctly female-centric narrative. First-time writers and directors Juanfer Andrés and Esteban Roel have created an exceedingly promising debut.

It’s Spain in the 1950s, and our main character Montse is a deeply Catholic, severely agoraphobic seamstress who has raised her younger sister after their mother died giving birth to her and their father went off to war and never returned. Theirs is a tense relationship. Montse doesn’t like it when her sibling comes home late from working in a local shop and she definitely doesn’t like it when she spies her chatting with a young man outside of their apartment building. To say that Montse is neurotic and possessive would be an understatement.

It’s not hard to understand that having both parents die and subsequently raising a younger sister would put a strain on even the most well-adjusted person, but it’s immediately obvious that Montse hasn’t been well-adjusted for a long time.

it’s immediately obvious that Montse hasn’t been well-adjusted for a long time.

Montse doesn’t have any friends except for one of her clients, Doña Puri, who gives Montse a little bottle of something to put in her water when she has “attacks.” Mrs. Puri is married to a doctor who has offered to help Montse get over her agoraphobia but she is simply too terrified to even attempt such a thing.

So when upstairs neighbor Carlos (the charmingly handsome Hugo Silva) takes a tumble down the stairs and bangs on Montse’s door for help before passing out from a head wound and the pain of a broken leg, it signals the imminent and literal crashing of all of Montse’s walls.

For such a staunch Catholic, Montse has a terrible habit of lying, not only to herself, but to Dona Puri, to Carlos, and especially to her younger sister, who is never named and always referred to as “the girl.” The Girl finds out about Carlos and is immediately smitten but also worried on his behalf knowing that Montse is not the helpful neighbor that Hugo thinks.

In the fine tradition of hapless characters with problems who unwittingly stumble into terrible situations by accident (think The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Eaten Alive),

the titular nest of the film turns out to be more like a trap

The dread and terror in Shrew’s Nest begin slowly and suffocatingly; we only ever see glimpses of the outside world and most of the film takes place in Montse’s apartment. We truly feel sorry for The Girl (a steely yet sympathetic Nadia de Santiago) who is trapped in this awful situation yet manages to remain strong in spite of everything. As Montse, Macarena Gómez is rarely still, constantly fluttering her hands, twitching and touching the heavy silver cross necklace she inherited from her mother like a talisman that is going to somehow protect her from harm. But who’s going to protect everyone else from Montse?

There are some huge reveals in Shrew’s Nest that make us sympathize with Montse’s plight and explain the undercurrent of weirdness that runs through the film. But by the time we find out the real truth, it is, of course, too late, not only for Montse, but for anyone who gets in her way.

The ending of Shrew’s Nest is definitely reflective of the time period in which it takes place, a time during the brutal, religious dictatorship of Francisco Franco, when women did not have much agency and their mental health issues were not well understood. The bleak ending of the film is ambiguous, but after all of the horrors we’ve seen in Shrew’s Nest, we sadly realize that it’s the only one that makes any sort of sense.

Shrew’s Nest does not currently have a release date.

Shrew’s Nest [Review]

Tension-filled

Shrew’s Nest is a tension-filled character study whose puzzle pieces slowly fit together as it builds to a grisly and horrifying climax.