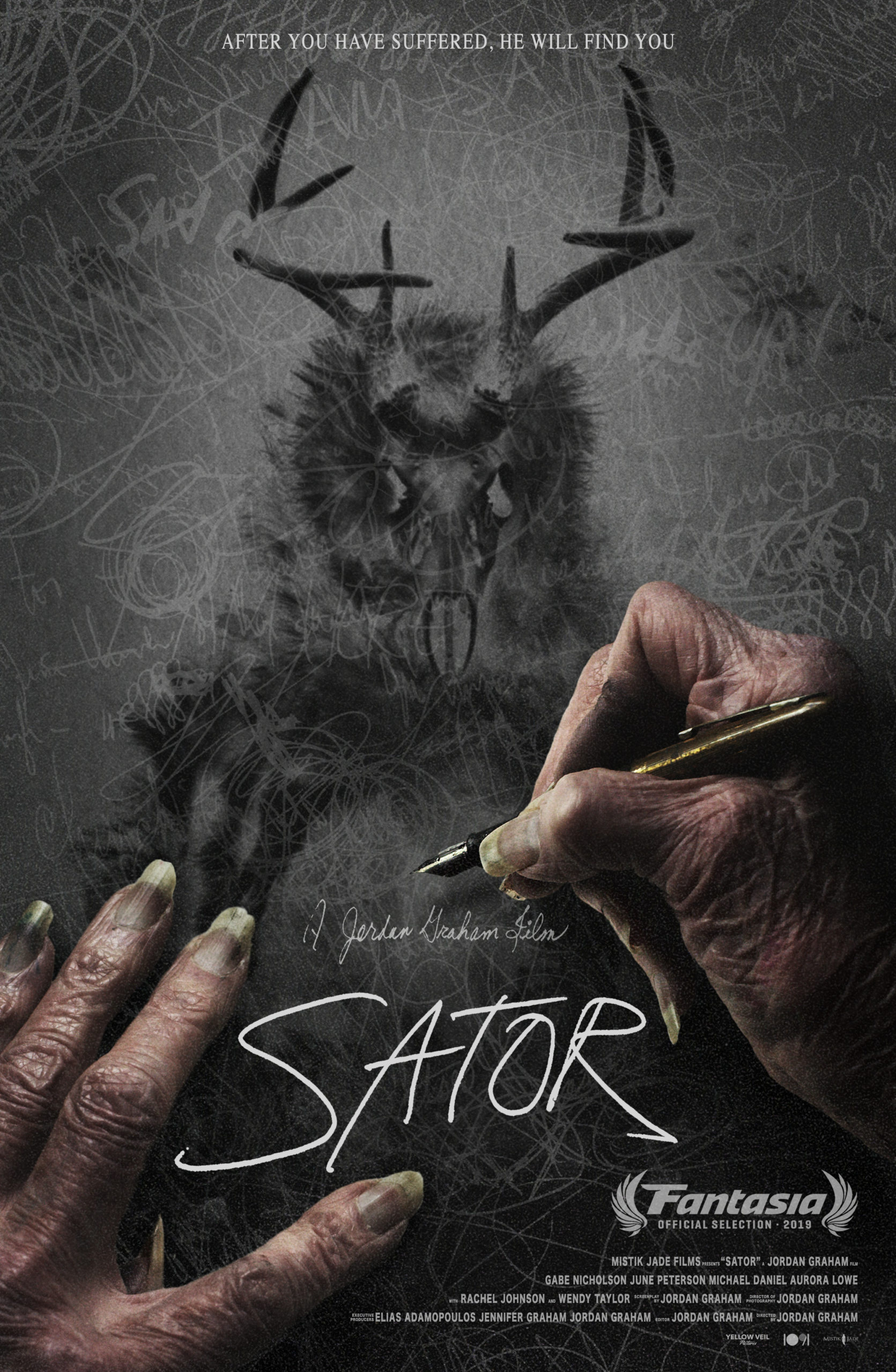

It’s been almost two years since I first saw Jordan Graham’s haunting film during Fantasia. Since then, I’ve enthusiastically sung Sator’s praises to anyone and everyone who would listen—despite not knowing when the movie would make its way to wider audiences. Thankfully, that time has finally arrived, with the film hitting digital and VOD this week.

Leading up to Sator’s release, I had the opportunity to speak with multi-hyphenate creator Jordan Graham. Check out our conversation, though beware—some spoilers lurk below.

My first exposure to Sator was at Fantasia in 2019. I was doing remote coverage for the festival and was trying to plan out what I’d be able to catch. The movie’s title caught my eye, as I was familiar with some of the word’s history in the context of medieval magical texts and esoteric Christian charms. When I read the description and saw the pictures posted, I was all in. After my credentials were approved, I got access to a press book with a statement from you, as well as some additional images and background on the film.

I created that look book that you’re talking about!

If I remember correctly, your email address was listed as the contact. One of the things that immediately stood out to me was how deeply involved you were with the film—how many roles you filled, how the the film grew out of what seems like a very personal experience that many people probably wouldn’t know what to do with, much less how they would they share that with the world. The look book mentioned how much time you had spent working on the film. I think the time frame was around five years.

Yeah, seven years total now.

That seems like a long path of creation. Then through the festival circuit and with the film finally coming to a wider audience, it’s taken up a huge amount of time. Can you tell me what that journey has been like?

It’s been rough and then rewarding, and then rough and then rewarding. To start with, I wasn’t trying to make a film that was going to take that long. I only wanted to spend around three years hopefully on it. But I was doing so much of it myself. I wanted it to look and sound a certain way, and to have certain qualities. It takes a lot of time to do. But wow, where do you want me to begin with that?

Well, let’s start at the beginning. It seems like the seed idea for the film came from these difficult experiences with your family background.

OK, so we’ll get into that then. OK, so Sator… I only knew Sator as an entity that my grandmother conjured up in 1968 through a ouija board that she brought home. Throughout that summer, so for about three months, she spent every day with him doing something called automatic writing, where she would have a glass of gin in one hand, and a pen in the other hand. She would just sit there and let Sator talk through her, and then she would write it all down. She did that over and over again for three months. At the end of that three months, she ended up in a psychiatric hospital.

for about three months, she spent every day with him doing something called automatic writing

I had no idea about any of this before I was making the movie. I mean, I’ve always known about Sator, but my understanding was that he was just like a guardian to her. So when I started making the film, my grandmother was never even supposed to be a part of this movie. Her story was never supposed to be part of this movie. I had a completely different script before I started shooting, and since I was on a budget restraint, I couldn’t find anything that looked as cool as the cabin that I built. I was trying to figure out where else we could shoot and I decided that my grandmother’s house looked pretty cool. Then I thought, let’s put my grandmother in a scene. We could do a quick little cameo, and that would be a cool way to memorialize her.

The first scene with her, I got with Michael Daniel, who plays Pete in the film. I told him, “You’re going to come in and meet my grandmother on camera. You’re going to pretend to be the grandson and talk about spirits, because that will get her riled up, and she’ll talk about it.” When he came in and claimed to be her grandson, she’s like, “I don’t know who the hell you are.” Then Michael started talking about spirits, and she brought up the automatic writing stuff on her own. I’d never heard about that before.

After that day was done, I went home and was looking at the footage and editing it. I was wondering what this automatic writing stuff was all about. I talked to my family about it, and I

felt like this was something really interesting. This was going to make the film a lot more personal and unique. I wanted to incorporate it more, and so I rewrote part of the film. Then I went back and shot more with my grandmother. But you can’t predict anything that my grandmother has to say. You can’t tell her what to say. She just says whatever she’s going to say about automatic writing and her journey with the voices in her head.

That wasn’t working for the script I had already written, so I spent a week rewriting. That process that would happen over and over again. Sator didn’t come into the film until I was in post production. At a point, my grandmother’s dementia was getting really bad. It wasn’t safe for her to be in the house anymore, so we put her in a care home. As we were clearing out her house, I found two boxes. One of them was a box of hundreds and hundreds of pages of automatic writing. My family thought they she burnt those years ago. So I found all of those and then I found another box with her journal. It was a thousand page journal documenting every single day of when she started using the ouija board to speak with Sator until she ended up in the psychiatric hospital. I was like, “Holy shit…” It was so unique and different, and so personal. I had to figure out how to get this in the film. I started thinking about how I could incorporate Sator into the film.

It was a challenge, as the dementia was getting worse for my grandmother. It became a race against time to get her to talk about Sator. I recorded maybe two or three sessions talking with her about Sator. She just kept talking about it. It was great. I got everything I needed, basically, for the opening of the movie. It starts with a closeup of her face and she’s talking about Sator. That was me basically filming her face for 40 minutes, and asking her, “Who is Sator, who is Sator?” and she didn’t remember him at that point. It’s just lucky I was to be able to have her share the voices in her head and the automatic writings. And being able to work it into my previous story that I’d created… It still blows me away that I was able to pull that off. And that’s just the story aspect of it!

A lot of her actual writings and drawings and scribbles—as well as some of those tapes that you recorded—made it into the film, is that correct?

Yes, everything that you see, all the scribbling you see, that’s all hers.

Including the drawings of faces?

I did not create any of that. That was all from 1968. That was really cool. I’m getting chills just thinking about that. For the tapes, I created some of the dialogue from what was on the pages, even though that’s those weren’t in real life. Some of those were Bible verses that were moved around to make it sound like it went with my story. The reason why I decided to use Bible verses was a bit of a personal thing that the audience would never get. You’d have to listen to behind the scenes material to know. During that time in 1968, my grandmother wanted to rewrite the book of Revelations and give it to children, so they could understand it better. My family was like, “Yeah, she was always wanted to rewrite the Bible.” So that was kind of my inspiration with the tapes.

And then with the home video footage, with the tapes… I wanted to have at least one flashback in the film that I wanted to shoot at that time on 8mm or Hi-8. I had hoped to shoot it on 16mm. I’d never done that before, but that was going to cost too much money. My mom went and got old Hi-8 tapes transferred to DVD. I was just watching them, and really just enjoying them. I wasn’t looking for anything for the film, but then I came to a birthday scene. A real birthday scene that happened 20-25 years ago. I’m in there but I’m like a little kid. I’m looking at this birthday scene in the house. It looks almost exactly the same. I mean there’s some plants that aren’t there anymore. But the house looks pretty much the same. It was great. My grandmother is off to one side of the screen, my grandfather is off to the other side of the screen, and then you have this middle section that I could totally create my own scene in.

During that time in 1968, my grandmother wanted to rewrite the book of Revelations…

So I went and I bought the exact same camera that these tapes were shot with. I bought the same Hi-8 tapes. I created a cake that looked very similar, I created presents that look very similar, and I shot a scene around that footage so I could incorporate it all into into the scene. I loved the Hi-8 quality. I love the black-and-white grittiness of it, and so then I just went out and kept shooting. Just different things, and a little bit ended up in the film. The credits are my favorite part. It’s just like a period of three or four minutes where she’s just saying all the perfect things and I’m just there. So she’s talking to me, and then when she stopped talking I’m just standing against the wall. And she’s staring at me and she’s quiet. She’s just sitting there, staring at me and I was like, “How long can I keep this up where she’s just zoning out?” I don’t know how long it lasted, but it felt like such a perfect way to close out the movie.

That kind of touches on a question that I wanted to discuss. Had you always planned on shooting on different formats and in different aspect ratios? Or is it just something that developed through the process?

It happened when we found those tapes. That was not something that I was going to do originally. But I love that Hi-8 quality. I had to have reasons behind everything, even if it only speaks to me. The audience might not understand it, but at least I know the meaning of it. I have a problem with memories. I will remember certain things, like certain places in my past. I’ll have a really good visual of it, then I’ll go and find a photo of that memory and realize that I just remembered the photo. I don’t actually remember that memory at all. That’s part of my reasoning behind using the Hi-8 tapes and the black-and-white, 4×3 aspect ratio. That’s just kind of how the character of Adam remembers that time period—kind of like in black-and-white.

Another thing from the production side that really stood out to me, both when I first watched the film and again revisiting it recently, is how much attention is paid to the sound design. The sound design is both immersive and eerie, especially because there’s so much whispering and things like that going on deep in the mix. If I remember correctly, the sound design was primarily your doing as well. Am I accurate on that point?

Oh yeah. The sound of the film was very important. That is, to me, my biggest accomplishment on the film because that was the one thing I was the most uncomfortable with. Everything besides my grandmother speaking in the film—everything you hear—is something I did in post production. Every little rustle of cloth, every little click, every little breath. A lot of the characters breathing in the film is my breathing. So every little thing that you hear I did in post. It took me a year and four months to do just that process alone. I had to learn how to do 5.1 mixing too, which I had never done before.

When the film was done, and when I got accepted into Fantasia, I wanted to listen to it in a theater environment. So I took it to LA and had this guy, who had mixed the movie Tangerine. So we’re listening to the film in the theater environment and I’m watching him take his notes. I’m thinking, “This dude’s been a professional for, I don’t know, a couple decades maybe.” When the movie ended, I had no idea what he was going to say. And he said, “Do you want to get into sound design?” That was that was the best compliment I received on this movie. I mean, that just meant the most to me. When we went to Fantasia, one of the people during the Q&A told me that the film had the best sound they’d heard at the festival. That blew me away. That screening was actually a real big theater environment, and it was the first time I really listened to it like in in that type of a world. It was so cool listening to it—I didn’t realize it actually sounded that good. I mean, I mainly mixed it in my bedroom, you know…

There were aspects of the visuals and how they interplay with the sound mix that reminded me of the work of David Lynch, who I’ve long been a fan of. When you were designing some of the more dreamlike visuals and how the sound affects the experience, did you have specific influences or inspirations that you were looking to?

I wanted to make a very quiet film, a very atmospheric, quiet film. I have a really hard time watching horror movies when the music is cueing me that something is going to be scary. As soon as that happens, all my tension is completely gone. I can predict when like a pop-out is going to happen. So I thought I would love to have a movie where the whole time, you just don’t know when something is going to get you. One of the biggest influences on that, and one of the scariest theater experiences I had, was No Country for Old Men, because there’s no music in that film—or very, very little. It gets so quiet that there is like a scene during a drug deal, and one of the characters just opens up a door and just the sound of that door opening made me jump. It freaked me out. I guess that was my main inspiration as far as sound design. As far as getting the the mood of the music, I love the credit song for Blair Witch, which is just basically like just sound effects. So I created the music. I mean, I’m not a musician or anything, but I had pots and pans and nuts and bolts. I had a bass guitar with a violin bow, and just made sound effects with that. And so that was it for music.

One of the things that provides the movie a real sense of scope that is juxtaposed with the personal nature of what’s unfolding in the story are the filming locations that you used. They’re absolutely beautiful, especially how over the length of the film you see drastically different changes in landscape with the passing of the seasons. I feel like that added a lot of production value to the movie, but did it also give you unexpected challenges that you had to overcome?

The locations weren’t really a challenge. I had no schedule on this film. I had one major rule on the film, which was no evidence of sun. I wanted everything to be soft and beautiful, and I had all the time in the world to wait for those weather conditions. When the weather conditions weren’t great, then we would just shoot in the cabin. The biggest challenge shooting on those locations was that I had a dolly track which was just made out of PVC pipe. The tripod sat on these wheels so that I was able to just get the smooth shots, but the PVC pipe wasn’t placed on anything, so you’d have twigs and dirt, and whenever you pushed the camera forward, it would jitter or get caught up. So I guess one of the biggest technical challenges while filming was using the PVC pipe to get a smooth shot, while making sure everything stayed in focus and that everything’s visually how I want it to look in frame, and making sure the performance is right. Sometimes I’d get a great performance and the camera would get stuck or something like that.

I had one major rule on the film, which was no evidence of sun.

It strikes me that at the very beginning the land is verdant and it’s foggy. Then later in the film, it’s snowy—the kind of stuff that that we don’t often see here in Texas.

I could tell you about the snow. I live in Santa Cruz, California, in kind of like a suburban area, but the forest is about half an hour away. Most of the movie was shot in the Santa Cruz Mountains, and then Yosemite. I shot for 120 days on this film. Most of it was in Santa Cruz, except for two days in Yosemite. On the first day we shot in Yosemite, I really wanted snow on the trees and for it to actually be snowing. I waited for a day when it was like an 80% chance of snow. I went up there with Michael, and it was just us. We drive up there; it takes about three hours to four hours to get there. We get up there and it’s not snowing or doing anything that I wanted it to do. Then you get that fox or wolf or coyote, whatever it was, in there. I did get like that opening shot of the snow, that beautiful opening shot, and that was it. But then we go home and I really wanted snow on the trees. Then we’re waiting. I’m waiting. I’m getting other shots, but I’m waiting and a couple months go by. Now we’re in March. There’s like a 50% chance of snow, and if we get any, it’s only going to be like half an inch. I didn’t care if it snowed any more. I had to get snow on the ground at least. So we decided to just go up there. We got up at like 2am, or something like that. We drove out there, and I couldn’t afford a hotel this time. We get there, and it’s still night time. It’s just snowing and snowing and snowing. I’m hoping it will stay like this until it’s light enough to shoot. So we’re out there just waiting by ourselves, and then the snow is getting packed up on the road. We didn’t have any chains on our truck. When it finally got light enough, I was able to get the first shot where you see the snow compacting on the trees and then collapsing. That was one of the first things that we shot out there in the snow, and just that took awhile too, ’cause like I’m hearing snow collapsing all over the place. I’m just like aiming the camera, trying to get it, and then luckily I got that one shot. Then we drove into Yosemite Valley, and the rest of the day it was just snowing the whole time, and getting up to your knees. It was just another just lucky thing with the weather. I know, it’s a long story, but that was both and challenge and a lot of fun.

Regarding the shot with the fox or whatever it was, was that just a happy accident on the day? It’s such a playful, unexpected moment in the film.

Yeah, so that first day it wasn’t snowing at first. So we drove around the Valley, which takes probably 15 minutes. We’re just driving around the Valley throughout the day, just hoping that maybe we’d get some like cool weather, but we kept seeing that fox or whatever it was. We kept seeing that animal, but there were always cars and other people looking at it. We had been driving around a while, and we kept seeing it. Then there was one time we got around and saw it there with nobody else around. We got out and followed it to the water, because the river was a prettier setting. We didn’t want to just get the road. But yeah, it was a happy coincidence.

I really liked that scene. So there were a couple more things that I wanted to ask you. Regarding the locations, at the beginning and then a little bit further into the film, there’s this huge stone structure. Do you know what that is?

Yeah, they’re lime kilns in the Santa Cruz Mountains. I’ve shot there quite a bit. Back in high school. I did a short film there, and there’s a lot of ruins around Santa Cruz. The big stone structure was in the Santa Cruz mountains, and then there’s the one with the waterfall, which was an old train tunnel. It’s in a totally different area, but kind of in the Santa Cruz Mountains still. That one had graffiti all over it, so I had to paint out all the graffiti, even underneath the waterfall was graffiti. So I had to figure out how to paint underneath the waterfall in Photoshop.

I like using Santa Cruz in my films. I call Santa Cruz “Midground” in my films. I like mentioning it here and there, and will in the future. I didn’t want to show anything of Santa Cruz in this, but I still wanted to have some Santa Cruz landmarks and that and like having these ruins in there.

Even for something that’s not a “traditional” character, the setting adds a lot of character to the film. The lime kiln especially cuts an imposing figure.

The idea of putting all that in there was just to make people wonder, “What is this? This ruined land… Who inhabits this ruined land, and what creatures are in this land?”

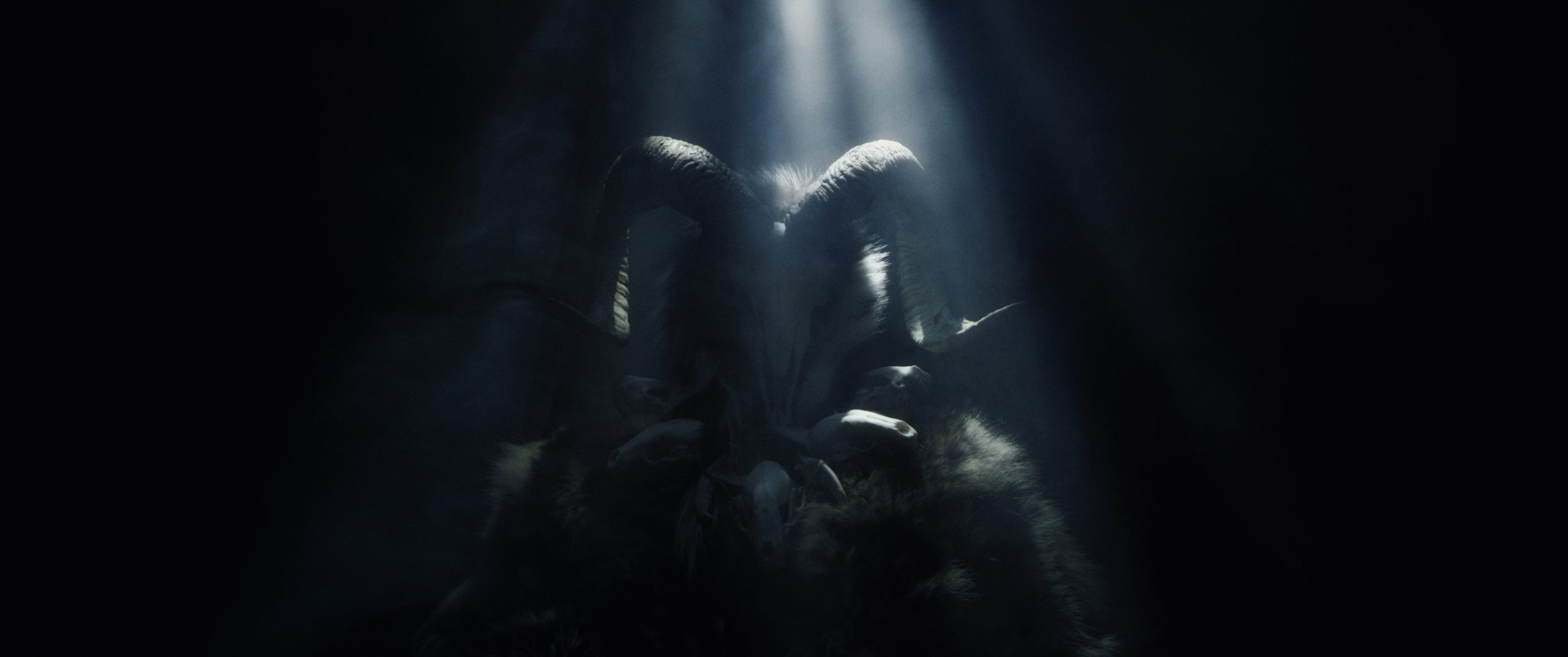

So we’re getting to a bit of spoiler territory… When we finally see the design of Sator and his disciples, the design of these entities is otherworldly, but it’s also grounded in reality. We see pelts, and bones, and things like that. How did that look develop?

The Blair Witch Project was a big influence on that. I love how you don’t see the witch at the end, and I wish I could have done that—but since the movie has kind of a slower pace, I felt like I would be cheating the audience if I didn’t show at least something. So I was asking myself how do I create this? How do I make the audience not see something, but still see something? And having them wear the forest, you still don’t know what’s underneath there. You don’t know if there’s a creature, or if it’s a human, or a spirit.

You don’t know if there’s a creature, or if it’s a human, or a spirit.

I came up with the look. It also goes with the sound, and of how the only animals that you hear in there are crows. You don’t hear one animal, you don’t hear one bird chirp or anything throughout the rest of the movie. My idea was that these creatures or entities killed the forest. They killed the animals in the forest, and are wearing the forest. That makes it more organic, and more real.

I love the image where he points, and his fingers are made of what appear to be jawbones. I have another question that falls into this spoiler territory. The last act of the film takes a pretty surprising turn. Up until a certain point, it’s very meditative and you’ve heard of things that have happened in the physical world, but at least for me as a viewer, I was questioning how much of this is physical? How much of it is mental? But then there is an event that firmly plants things in reality. This is real, and the stakes are very real. How did you approach that? Was that always part of the story of the film, or is that another thing that that grew and changed out of necessity?

Well before that, like the first bit with Adam’s main story, that is kind of like the dream. We don’t know if it’s real or not. Then we get into the snow section, and to me that is the more grounded and the more real aspect of the film. Yes, the character Pete was always supposed to die. I don’t remember how he was originally supposed to die, before I settled on the deer antler.

When I decided I wanted to do the deer antler, all that was supposed to happen was the deer antler would go into his throat, then he’d be stuffed into the furnace, and that was it. But then the week before we shot it, Michael came to me and he’s like, “Dude, I’ve been growing the beard out for this movie for seven months. I want to burn it off.” and I was like, “Nope, that’s way too dangerous, and it’s not going to happen.” But then I was thinking about it, and fire is such an important theme to this movie. I thought it would be so great if we could figure out how to do that.

The day that we shot that scene, he came over. I had him fill out a release form, which basically said “If you get hurt, this is on you. This is what you wanna do, not me.” Then we hooked up the blood pump to him. First we did the jamming of the deer antler in there. We did a few scenes of that, and then it came to burning it. We were trying to light his beard on fire, but he was so saturated in blood that it wouldn’t light on fire—it would just singe a little bit. I went across the street to my neighbor’s house and borrowed some lighter fluid. We just brushed lighter fluid on his on his beard, and then that’s why there were three people on set that day. So I had 120 days of shooting, and most of the days were myself and one other person. I mean with myself and the actors. I had a few days with one person assisting me. That day I had three people assisting me. One was to light the beard, another one was to put the beard out with the hose. We had somebody with a lighter, somebody with a hose, and then Michael’s wife was there with the blood pump. I just had her squeeze the blood pump, and we did that in two takes. He’s only on fire for like half a second but we did it in two takes, and I used both those shots. There’s like a cut right in the middle, and I used both of the shots in there.

It’s a very intense moment in the film.

Yeah, it definitely is. Especially when it’s been so quiet and dreary and atmospheric, then you get to that huge like. “Oh shit—I wasn’t expecting it to be that type of movie” moment.

There’s one last question that I wanted to ask. Some of this may just be my memory playing tricks on me, but have there been some slight changes to the film between the version that played at Fantasia and the version that’s coming out now? I thought there were a couple of things that I didn’t remember, but so much time has passed since then. I wasn’t sure.

I tried shortening up the film for Fantasia, and there were some glitches in there. When I fixed them, it made it a little bit longer, but I think it’s pretty much the same.

Like I said, a lot of time has passed and it could just be my memory, but there were a couple of a couple of quick that made me stop and question myself about whether I was remembering correctly. In one of the shots, a character is looking out into the sky and you can see a star. It looks like sunrise or sunset, and then a moment later, that star is completely gone from the sky.

The star goes across the sky. That was there originally. Here’s how I did that… I was in my garage and there was a little little light peeking through. I basically had the camera on it and I move the camera back and forth so it looks like it’s moving, but it just leaves a natural trail. I kept the camera, still on the little light, and then moved the camera quickly and it just makes a trail and the trail moves across.

As we’re wrapping up, I want to say thank you for taking so much time today to talk to me. This has been one of the films that, for a year and a half now, when people ask me for horror recommendations, the first title that usually comes out of my mouth is Sator. For so long, I didn’t know when I was going to be able to see it again, much less when the broader audience would be able to see it. So I’m really excited that they’ll get the chance soon.

I am too. I’m very thankful for Yellow Veil to reach out to me, and to get this thing moving, and to have interviews like this.

Sator hits VOD and digital on February 9th. Don’t miss it!