Art tends to imitate life when it comes to violence in horror films. In most cases, there’s a reason for it—a monstrous creature acting out of instinct, a self-perceived victim lashing out at would-be oppressors, a mentally unstable person with a faux moral high ground.

But sometimes there isn’t a reason. Sometimes violence chooses a time and a place and waits for someone to come along. This is often the most effective form of horror; The Strangers made waves with its random yet calculated brutality, and Funny Games set the tone before that with deranged neighbors who break the fourth wall to give commentary on their unspeakable acts.

With Coming Home in the Dark, New Zealand has entered the conversation on arbitrary savagery. And with it comes Daniel Gillies, one of the leading candidates for Villain of the Year. (Someone has to be keeping track of that category, right?)

It’s not so much about what happens—it’s about how it happens, and perhaps why it happens, if the “why” can even be explained.

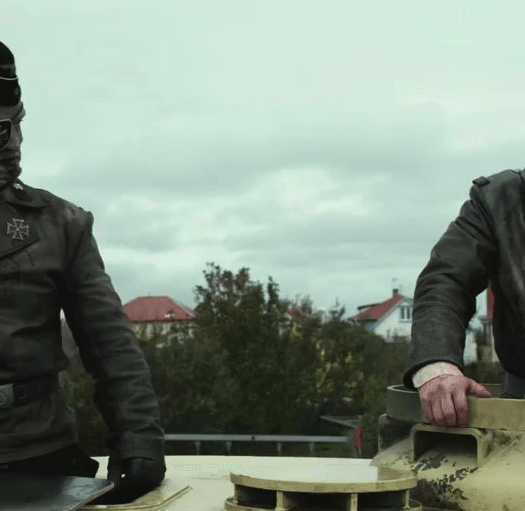

The story begins, as all tragedies tend to, with a picture of innocence. A family of four, traversing the New Zealand countryside on vacation, pulls over at a picturesque waterfront to relax and enjoy some fresh air. Then, like a tumbleweed in the desert, two strangers show up not only ruin their day but potentially their lives.

It’s not much of a spoiler to say that things don’t go well for this family of Kiwis. But in a film like Coming Home in the Dark, it’s not so much about what happens—it’s about how it happens, and perhaps why it happens, if the “why” can even be explained. The “why” here all comes down to Mandrake (played by Gillies), the breezy and inquisitive psychopath with an assault rifle who has deemed this family worthy of physical and emotional torture (and possibly worse). Gillies is swaggering, unflappable, and smarter than he seems at first, delivering all the ingredients needed for a compelling bad guy.

Mandrake and Hoaggie are terrific as the cat and mouse, often trapped in the same cage.

But again, his most compelling quality is that he holds all the answers. As the sun sets and the group ventures down the highway and into the night, Mandrake assumes the role of interviewer to Hoaggie (played convincingly by Erik Thomson), peppering him with assorted questions about his work, his past, and his philosophies. As the conversation evolves and takes a turn, the “why” is slowly revealed and then pulled back until it’s up to the viewer to decipher what exactly is motivating these heinous acts.

Coming Home in the Dark is a film that promises no easy answers, but it does deliver a thrilling journey. Mandrake and Hoaggie are terrific as the cat and mouse—often trapped in the same cage—and the obstacles along the way to the final destination serve to expand the circle of violence and loosen Mandrake’s hinges. And while the film may not leave you in high spirits, it’s certain to leave you affected by what you’ve witnessed.

Daniel Gillies is the Villain of the Year in the Brutal, Bleak ‘Coming Home in the Dark’ [CFF 2021]

Brutal

Coming Home in the Dark is a meditation on seemingly random acts of violence, offering a thrilling journey and a compelling villain without any easy answers.